Whether a Parody Defense is Valid depending on How a Mark is used

Using a mark which is similar to a registered trademark and used in relation to goods or services identical with or similar to those for which the registered trademark is designated to cause likelihood of confusion among relevant consumers constitutes trademark infringement. Nevertheless, parody is an available defense against such trademark infringement in Taiwan. For the sake of freedom of speech, expression and artistic creation, the enforceability of trademark rights may be reasonably limited if certain requirements for fair use are met. Parody has been recognized as a legitimate fair use defense in the judicial practice. In one recent case, the court revisited the factors and criteria for determining a valid parody defense.

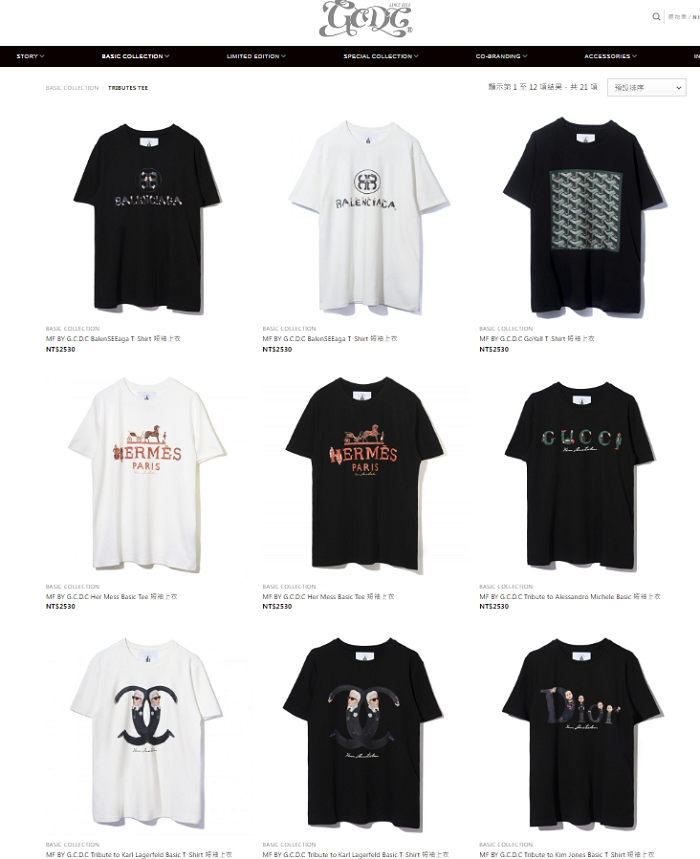

Huang and Yen (collectively referred to as “the Defendants”) ran an online store on Shopee, Taiwan’s leading e-commerce shopping platform, offering for sale counterfeit clothing, luggage and other apparel bearing marks similar to those owned by Louis Vuitton, GUCCI, Chanel, YSL, Balenciaga, Dior, Burberry and Hermes (collectively referred to as “the Complainants”). The Complainants discovered the alleged infringement and reported it to the police, who subsequently raided the Defendants’ physical store and seized more than 2,500 allegedly infringing items. The prosecutor filed charges with the Taipei District Court.

In the trial, procedurally, the Defendants argued that the series of Counterfeit Characterization Reports submitted by the Complainants in support of their counterfeit accusation carried no evidential capability because they had been produced by third-party IP companies or law firms rather than by the prosecutor or the Court itself; the Court denied this argument. Specifically, the Court emphasized that the prosecutor’s office is allowed to pre-select a number of candidates comprising various investigatory experts and organizations for characterization. When a criminal investigation is required, the police would then be able to entrust one such expert or organization to conduct characterization. This approach has been affirmatively adopted in judicial practice.[1] Determining the authenticity of luxury products in a trademark infringement dispute generally requires special knowledge in the fashion industry; government agencies such as the criminal investigation bureaus do not have the expertise to verify the authenticity of luxury products. To this end, the characterizations produced by professional entities such as IP companies shall be respected. Therefore, the Counterfeit Characterization Reports submitted by the Complainants serve as valid evidence.

The Defendants raised a parody defense, arguing that the designs and logos printed on the seized products which allegedly bore a similarity to the registered trademarks were secondary creations, or derivative works, sold under their own brand unrelated to the Complainant’s brands. After the analysis, the Court determined there to be a likelihood of confusion and rejected the Defendants’ parody defense.

As mentioned previously, for the benefit of the trademark owner, the use of a similar mark on similar goods or services, which may cause confusion among relevant consumers, constitutes infringement. The Court highlighted that as to whether there exists a likelihood of confusion between the senior registered trademark and a junior mark, it would examine multiple factors comprehensively, including (1) the level of distinctiveness of the trademark; (2) whether and to what degree the trademarks are similar; (3) whether and to what degree the goods or services are similar; (4) the level of business diversification of the trademark owner; (5) whether there is actual confusion; (6) the degree of familiarity with each trademark among relevant consumers; (7) whether the junior mark owner is acting in good faith; and (8) other factors leading to confusion.

As the Court emphasized, public interest in the avoidance of confusion and public interest in free expression are equally important and should be balanced when potential conflicts arise. The legislative purpose of the Trademark Act is to protect trademark rights and consumers’ benefits so as to maintain fair competition in the market as well as promote the positive development of commerce and industry. The trademark system is designed to allow a trademark owner to gradually establish its brand value through the continued use and maintenance of a trademark, while relevant consumers can rely on the distinctiveness of trademarks to identify the source of individual goods or services. Since trademarks entail both the public interest in avoiding confusion among consumers and the private commercial interests of the trademark owner, a defense against infringement must not simultaneously compromise these interests. A valid defense of parody involving the imitation of a well-known trademark must be entertainingly humorous, satirical or critical and must convey two contrasting concepts simultaneously, the Court elaborated.

The Court further reinforced its analysis on the basis of foreign comparative law. The success of a joke depends largely on language, culture, social background, life experience, history and other factors; in many cases there is a barrier preventing a person from one culture understanding the humorous nature of a joke from another culture. On the contrary, whether relevant consumers are likely to be confused is decided the moment they see a mark without much deduction or thoughts. The criteria set forth by the court of the My Other Bag case[2] were that a valid parody defense must show that “there is clearly no connection to the original mark” and that “consumers can immediately identify the accused product as a parody.”[3] To sum up, a valid parody defense must simultaneously express the meaning of the original trademark and the humor, satire or criticism of the imitated work; by having these contrasting concepts presented to them, consumers can clearly understand that the imitation is a joke that has relation with the original trademark. Additionally, the balance of public interest between confusion and free speech is another critical factor to consider.

In the present case, the text, designs and logos on the seized products were found to be similar to the registered trademarks in dispute. Consumers with ordinary knowledge and experience may mistakenly believe that the products came from the same or related sources when paying even the slightest attention; taking this into account, it can be concluded that the logos are similar to the registered trademarks. Furthermore, the seized products are identical or similar to the goods to which the registered trademarks apply. The Complainants are well-known and reputable, with a long and rich history specializing in high-end luxury fashion products. Their trademarks possess a high degree of distinctiveness and demonstrate quality and good will. Relevant consumers would have mistakenly surmised that the seized products were provided by the Complainants. There is no entertaining aspect of humor, satire or criticism inherent in these products. To briefly conclude, the Defendants failed to establish a parody defense of the infringement accusation.

The judgment in this case is consistent with the precedent cases for the analysis of parody in trademark infringement issues. It is worth noted that the factors of the My Other Bag case have been recognized by the Taiwanese courts; they are applicable standards to predictably assess whether parody can be established in a future case.

The Tributes series: t-shirts examples at an official website of Defendant Huang’s brand “MF BY G.C.D.C.” As the designs on the t-shirts show modification of major luxury brand’s trademarks, MF proclaims to feature recreation and controversy mingled with street elements in its products. To disclaim, the t-shirts on this snapshot are not necessarily the same as those seized and disputed in this case.

[1] SC-96-TaiwanAppeal-No.2860

[2] Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A. v. My Other Bag, Inc., 16-241-cv (2nd Cir., Dec. 22, 2016)

[3] IPCC-108-CivilTrademarkAppeal-No.5