Supreme Court: A Derivative Work Created by Unauthorized Alteration of Another’s Work is Copyrightable

Whether a derivative work made by modifying an existing work without permission from the original author—possibly constituting infringement of the original author's alteration right—is eligible for copyright protection has been a long-pending question. There have been conflicting viewpoints among the IP community, legal academics and the judiciary, since statutory law has remained silent on this. Recent cases have refused to protect such derivative works on the grounds that doing so would be no less than to encouraging infringement activities. However, in a January 2024 judgment, the Supreme Court decided to affirmatively recognize the copyright eligibility of a derivative work made from materials without permission.

Eastdawn Trading (the “Complainant”) sells beauty products by way of a series of advertisements and videos on various social media platforms. Upon finding that Huang (the “Defendant”) and his company were selling similar products using similar advertising phrases, pictures and video clips (as shown in Table 1), the Complainant filed a criminal charge against the Defendant in ancillary with a civil action asserting copyright infringement.

The Defendant argued primarily that, among other things, the Complainant did not own the copyright for the allegedly infringed advertisements because these were simple modifications and arrangements of others’ materials for which the Complainant did not demonstrate a legitimate authorization from the source. The District Court ruled in favor of the Defendant, reasoning that the copyright of the asserted advertisements failed to be established.[1] On appeal, the IPC Court reversed the lower court’s judgment upon finding that the Complainant had acquired the copyright for the advertisements at the time they were created.[2] Not satisfied with the reversal, the Defendant brought the case up to the Supreme Court. Contrary to the Defendant’s wishes, the Supreme Court dismissed his case by holding that the Complainant’s advertisements are copyrightable works even if they have been made from others’ materials without permission. The judgment suggested that another party can be potentially subject to criminal penalties and liable for civil compensations due to an unauthorized reproduction of the advertisements.[3]

The Supreme Court began its reasoning from the constitutional basis. The Constitution of the Republic of China clearly stipulates that people have freedom of speech, lectures, writings and publications. Echoing the provisions on freedom of writing and publication, the Copyright Act aims to protect the rights and interests of authors, to coordinate social and public interests, and to promote the development of national culture. These three pillars are equally important and should be maintained in harmony. In the interpretation of the Copyright Act, when there is a conflict of interest between the general public and the author, special attention should be paid to the balance between the two so as to avoid hindering the development of culture.

Most importantly, regarding the way in which a derivative work is defined, the Supreme Court stressed that whether a work is copyrightable does not depend on the creative process or the mental state of the creator. The Copyright Act stipulates that a derivative work is a creation that is an adaptation of an original work and is protected as an independent work. A derivative work differs from a non-copyrightable plagiarized work in that it demonstrates originality and expresses the uniqueness and personality of the creator. Hence, a work is impartially entitled to copyright so long as the copyright requirements or definition are met. The secondary fact that a derivative work was created without prior consent or a license determines only whether the creator is subject to criminal or civil liability. In this way, conflicts of interest between the public and the original author are fully reconciled. The Court noted that this is a constitutional interpretation of the derivative works clause in conjunction with the policy objectives of the Copyright Act and the freedom of writing.

The Court further found that the government has also taken the position of setting aside the element of the creator’s legitimacy when determining whether derivative works qualify for copyright protection. A previous administrative letter from the Ministry of Interior Affairs stated that in a case where a translated work was made without permission from the copyright holder of the original work, the translated piece (a derivative work) was another independent creation and was also protected by the Copyright Act. The author of the original work would have to seek legal remedies separately. In another previous case, the IP Office held the view that the ownership of a newly generated script and film belonged to the person who modified the original work, if no prior contract had otherwise been agreed, and the script and the film were protected independently as derivative works. These examples demonstrate that, from the consistent viewpoint of the government, the protection of a derivative work does not require authorization as a necessary element.

Comparative law provided another legal basis for the Court’s analysis. The old copyright law of Japan recognized that only a derivative work from a legitimate alteration could be protected. However, this clause was deleted in 1970, as the majority of scholars opposed it. Taiwan’s Copyright Act was primarily formulated with reference to the new Japanese law; both interpretations are in agreement that a legitimate alteration is not a requisite element for a derivative work to be protected by copyright. Furthermore, the Court refused to adopt the policy objectives of the Berne Convention[4] and its US counterpart[5], both of which differ from Japanese law in that they require the permission element to protect a derivative work; the Court emphasized that the legislative background of Taiwan’s Copyright Act is different from these two.

Lastly, in addition to the issue of permission and legitimacy of the creator for a derivative work, the Supreme Court also briefly resolved the matter of whether a commercial slogan or phrase is protectable. As the Court explained, the advertising purpose of a commercial phrase is to attract consumers’ interest in purchasing by distinguishing its products or services from others. As a general practice, a commercial phrase must be concise in order to efficiently convey the purpose, effectiveness and uniqueness of the advertised product. The law may not deny copyright protection to a phrase simply because it is short. In other words, as long as a commercial phrase is not a commonly used expression or single term but is able to demonstrate a creator’s personality or uniqueness, it should meet the originality requirement and thus still be protected by the Copyright Act.

The Supreme Court concluded that the lower court was correct in its reasoning and assertion that permission is not a requisite to protect a derivative work. The case was therefore affirmed.

Table 1. Comparison between the Complainant’s advertisements and the Defendant’s accused images

|

The complainant’s advertisements |

The Defendant’s images |

|

C1

|

D1

|

|

C2

|

D2

|

|

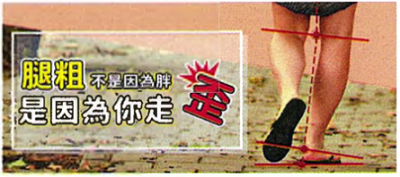

The text in both the C2 and D2 snapshots transliterates as: “having thick legs are not because you are fat but because you walk crookedly.” |

|

|

C3

|

D3

|

|

C4

|

D4

|

|

The text in both the C4 and D4 snapshots transliterates: “(You can) slim down your legs by (simply) walking the right way.” |

|

[1] 110-IPSummaryAppeal-No.1 Criminal Judgment, Taiwan Tainan District Court

[2] 110-CriminalIPAppealSummary-No.75 Criminal Judgment, IPC Court

[3] 111-TaiwanAppeal-No. 5457 Criminal Judgement, Supreme Court

[4] Article 2(3), Paris Act 1971, The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

[5] 17 U.S. Code § 103(a)